The continuous rise in real estate prices and housing precarity have turned attention to the search for alternative models of collective ownership and accommodation as a response to the commercialisation and financialisation of housing, the intense profiteering in real estate and in the city, and the shrinking of public policies to ensure the right to housing for those excluded from the market. Cooperative housing, although a small part of the housing market in most countries, is increasingly seen as a more democratic, lower-cost, and less commodified model of housing.

What is it?

Cooperative or collaborative housing refers to different forms of collective ownership that restrict real estate profiteering and democratic housing administration. As with all Social Solidarity Economy (SSE) projects, these are efforts that arise from the desire of a group of people to join forces and co-manage their resources to meet their housing needs, based on the principles of solidarity, reciprocity, inclusivity, and respect for the environment. Residents choose cooperative housing not only for economic reasons but for social reasons as well. Thus, cooperative housing is not just an alternative model of access to housing but also a field of experimentation for different ways of dwelling and coexistence, sustainable architecture and living, and collective intervention in the neighbourhood and the city.

How does it work?

Traditional housing cooperatives are shareholding companies that possess and provide residencies to their members. Residents acquire the right of use (not ownership) of their home by purchasing a share equal to the value of the property, which they can resell with or without capital gains, depending on the terms of the cooperative. In recent years, as it has become difficult for many people to raise the initial capital for the purchase of the cooperative share, interest has turned to models of non-profit rental cooperatives, where the right of use is acquired by paying an initial registration fee to the cooperative (purchase of a share regardless of the size or value of the dwelling) and signing a lease contract.

Since 2010, different cooperative housing projects have started to develop in Europe, each time adapting their organisational structure, legal status and financial instruments to the local context. In each case, they follow a democratic system of collective decision-making and participation in the management of both the real estate and everyday life; they seek to limit the profiteering of real estate by proposing a different concept of urban development and urban upgrading processes; they develop different forms of solidarity and support for members with low incomes or belonging to vulnerable groups. Many of these projects also involve the public sector to a greater or lesser extent, at the central, regional or local level. Typical examples are the Community Land Trust Brussels, the Meitshauser Syndikat network in Germany, the Sostre Civic cooperative, the recent attempt by the municipality of Barcelona to promote right-to-use cooperatives, and many more.

How can it be supported by the public?

Given the high cost of land and the large upfront capital required to build or repair a residential property, the role of public policies in supporting such ventures is critical, especially when targeting low-income members with no equity. In particular, municipalities or the central government can:

- Provide land or buildings available for use by the cooperative, applying the use right, where ownership of the land remains in public ownership but is granted on a long-term basis (usually 60 to 90 years) to the cooperative, which repairs or constructs, and uses the buildings, or through programmatic partnerships to grant property for public benefit1.

- Facilitate access to finance by providing guarantees or setting up special financial funds.

- Facilitate implementation through institutional reforms that will make it easier for cooperative housing associations to manage real estate (special tax regime, special regime for access to financial programmes, etc.).

- Promote partnerships between the public and social sectors for the production of affordable housing2 and subsidise the participation of low-income people and projects in housing cooperative ventures.

Do we have housing cooperatives in Greece?

In Greece, housing cooperatives, in the form we are discussing here, have not been developed, while at the same time the country did not have—and still does not have—a coherent housing policy. Nevertheless, aspects of public policy related to these cooperatives can be traced. As early as the interwar period, the instruments developed in the context of housing policy included the promotion of cooperatives by facilitating access to land and finance, mainly by adopting the model of garden cities and cooperatives that had begun to develop in France and Germany3. In the end, these frameworks benefited only certain categories of people, such as civil servants, who ultimately gained access to land but not to any funding.

The building cooperatives, in the form we know them today, are an evolution of these directions. The legal framework evolved in parallel with the institutionalisation of cooperative law in Greece as a special category of civil cooperatives. The institutional framework was finalised in 19874 with particular reference to the housing rehabilitation of their members or the improvement of the environment in existing settlements. These cooperatives are a form of private urbanisation and can be established for access to primary or holiday/secondary housing. They can be formed to provide their members with plots of land to build on, ready-made houses, or both; in essence, they are a mechanism for low-cost housing construction, with the cooperative being dissolved after the completion of its purpose and the transfer of the horizontal properties to the members. As has been documented, historically, it has been one of the ways of urbanising periurban land, operating mainly through mechanisms of appropriation of natural and social capital5, clientele networks, and serving particular interests. The trespassing on lands designated as natural protection areas by the 1975 Constitution prevented many cooperatives from moving forward. Today, they remain a pending issue to be resolved, but their purposes are not linked to the cooperative principles or the housing needs of their members6.

It remains a challenge for Greece to strengthen and develop cooperative and collaborative forms of housing, both by creating a supportive framework and by activating grassroots groups and associations that will imagine and experiment together with new forms of housing and living together.

And to return to the question of the title: Yes, we believe that cooperative housing in Greece is not only possible, but absolutely necessary!

Footnotes

- 1

The concession of real estate to SSE actors free of charge for five years to serve the social or collective purpose of the actor is already provided for by local government law 4555/2018. In the case of a concession to a housing cooperative, the concession is required for a longer period (60 years in Zurich, 75 years in Barcelona).

- 2

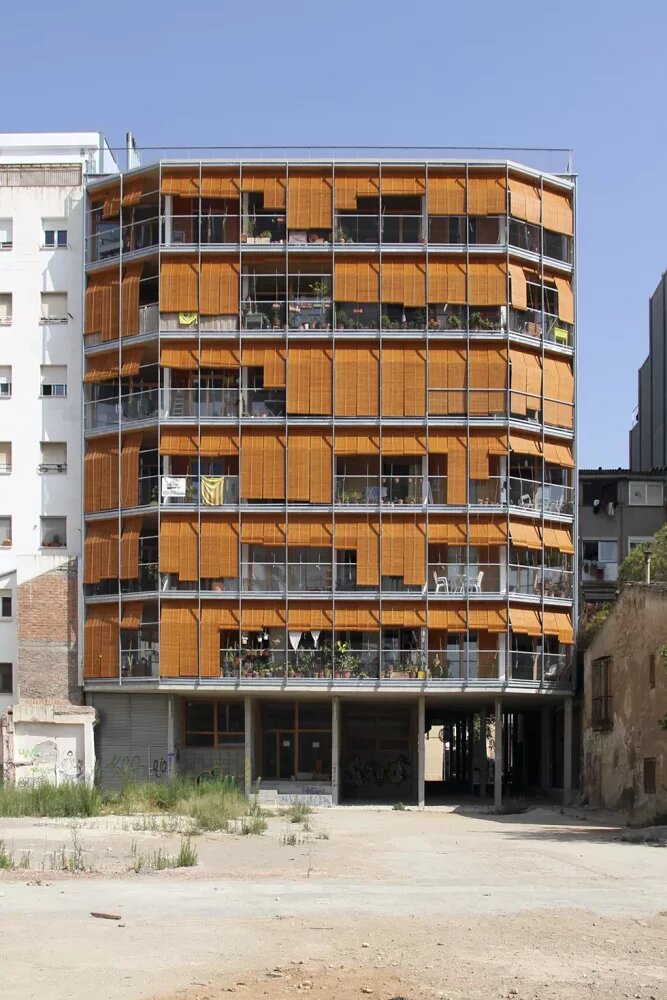

This model is applied in the large cooperatives of Zurich and more recently is being tested in the municipality of Barcelona. One of the first projects built after the Barcelona municipality’s bid is the La Borda cooperative.

- 3

Kafkoula, Κ. (1994), “In search of urban reform: co-operative housing in interwar Athens”, Urban History, 21, pp 49-60.

- 4

PD 93/1987 “Reform and unification of legislation on building cooperatives, the way they are organised, administered and operated and the urbanisation of lands belonging to building cooperatives and building associations”, as amended until 1991.

- 5

Many cooperatives have acquired or bought land that was designated by the 1975 constitution as natural protection (mainly forest land), preventing them from urbanisation since then. According to reports, it is estimated that there are more than 200 cooperatives in suspension involving more than 150.000 members.

- 6

Regarding the historical role of cooperatives, a very interesting article in Greek is “To syllogiko epos ths oikopedopoihshs” [The collective epos of land consolidation] by L. Economou, 20/05/2018, EFSYN.